Water is a precious resource, and worldwide demand continues to rise inexorably. Many launderers are still wasting this vital commodity unwittingly, especially those using washer extractors. This month we look at the significant financial and productivity opportunities that exist, which can readily be realised. Charges for effluent volumes and for effluent treatment are set to rise steadily at well above the rate of inflation in the UK and worldwide, in order to allow the considerable investment needed to protect rivers and oceans, so now is the time for action. The good news is that realising the opportunities is unlikely to need much investment, just sound management and some key information.

Modern process design has radically changed the optimum wash process for anything with oil or grease attached. Firstly, low temperature washing has become essential to avoid unaffordable energy costs, and every laundry should by now have eliminated the vigorous wash at high temperature using lots of alkali. This worked well enough in its day, but the advent of low temperature systems, at 40C and below, has effectively superseded it. The secret to getting these to work for you lies in the low temperature emulsification system, which must be matched to the hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) values of the oils and fats to be removed. With the right emulsifier mix it is possible to dislodge even the most stubborn grease stains from polyester fibres, completely and every time. The best, broad-range emulsifiers will even take out spa treatments and nut oils, with HLB values going down as low as 6 or 7.

There is still a need for high alkali processes for a few classifications and for activation of low temperature oxygen bleaching systems, but if you have not already done so then now is the time to review your processes, in conjunction with your detergent supplier.

Cooldown can now be eliminated, because there is no risk of crows’ foot creases from thermal shock at 40C. This produces further savings both in water (cooldown is a thirsty requirement) and more importantly for many, productivity (by shortening the cycle time).

Pressure creases, especially on polycotton blends, are a key quality issue for garments and table linen, but at 40C they cease to be a major problem. The creases are set in the hot wash, because the polyester is softened at high temperature and the creases are quickly set in. At 40C it is usually possible to operate with a lower dip in the main wash, in the range 75 – 100mm instead of 125 – 175mm. This brings a further chunk of water saving, a little more energy saving and a potential reduction in wash chemicals, along with another small productivity benefit.

Rinse dips have been mentioned several times by LCN as a widespread opportunity for economy. Many washer extractors are set up to wash and rinse successfully anywhere in the country of sale, despite the water quality varying widely from region to region. The default rinse dips will cope successfully with even the poorest, very alkaline water quality. However, anywhere with decent water will almost certainly be using unnecessarily high rinse dips. With a little help from the detergent supplier (who should be equipped to measure last rinse alkalinity) it is possible to optimise every rinse dip on every machine and create some quite surprising savings.

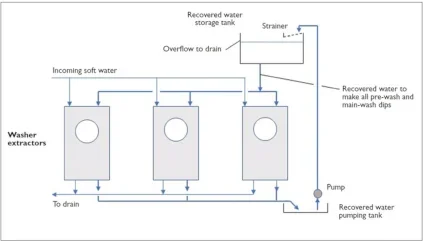

Last rinse recovery has been described in previous issues of LCN. This will usually reduce the volume of water required for the washer extractor washhouse by another 30%. There is some expenditure on valves, pump and storage tanks, so this should only be considered once the earlier economies have been realised. The principle is shown in the diagram.

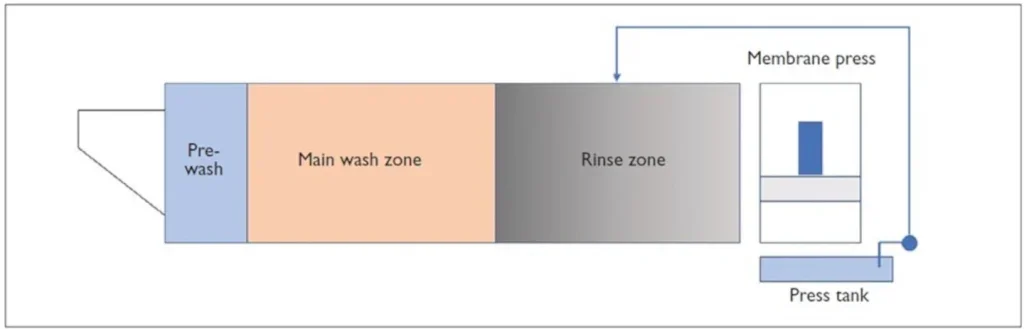

Split rinsing: for users of tunnel washers, the benefits of split rinsing have not yet been fully realised. It is possible to greatly improve the effectiveness of the first half of the rinse zone by taking an additional pumped recycle from the press tank back into the centre of the rinse zone. The saving of about 2 litres per kg of textiles can be readily obtained on any tunnel with a double skin to the rinse zone, or with other means of achieving the necessary injection (see diagram).

Further steps: so far in this article we have concentrated on steps that require no investment, just careful management. The following steps should be considered once you have implemented all of the free ones!

Water quality continues to be a major problem in Southern and Southeastern England, with alkali from chalk strata and iron from a variety of sources. Ion-exchange softeners take out the calcium and magnesium salts to optimise detergency and help prevent greying, but they don’t remove the alkali radicals, so the more alkali there is in the raw water, the more rinse water is required.

There is no economically attractive pre-treatment to remove the alkali, but there are a few wash processes which utilise acid neutralisation of alkali to significantly reduce rinse water requirement. If these are expertly installed and managed, they will reduce water consumption considerably, although they are generally applied in a tunnel washer, rather than a washer extractor.

High iron levels are even more serious because iron accelerates the damage to cotton caused by chlorine bleach, and it also contributes to greying and yellowing of white work. Consequently, removal can be very worthwhile. If the level of iron exceeds 0.1ppm (that is just one-tenth of one part per million!), then the operating cost and quality benefits of removal outweigh the investment cost. This is achieved using a small ion-exchange unit that works on the same principles as a water softener and converts all dissolved iron to iron oxide particles. These are then filtered out over a fine carbon filter. The benefits consist of lower chemical damage from chlorine bleach, less discoloration and better water softening and resin life (by avoiding iron poisoning of the softener resin).

Effluent volumes are still estimated by the water company in many regions, by taking the metered inflow of raw water and applying an ‘evaporation allowance’ to this. The allowance can be checked by taking the amount of water evaporated in the dryers and on the ironers and expressing this as a percentage of the raw water used. If the calculation is performed after the economies suggested in the first part of this article have been achieved, this will maximise the evaporation percentage and therefore minimise the estimated effluent volume. Some water companies allow only 2½% evaporation allowance, others allow 4% but if you calculate your figure accurately you could well make substantially greater longterm savings. Users of tunnel washers can frequently justify over 10% for evaporation and at least one has been getting 25%. The necessary calculation is not difficult.

Metering of effluent volume is possible using a flume and calibrated level device, but it must be kept clean daily to ensure accurate results and it does require some investment (usually £2000 – £5000 depending on the building work required). The responsibility for funding the cost of a flume is rarely taken by the water company – it is deemed to be a laundry cost.

The Mogden formula is used in a great many regions to calculate your fair share of the cost of treating effluent. The equation has four components covering reception into the sewage pipe network, primary treatment, chemical oxygen demand (usually for the biological treatment, but chemical demand is easier to measure) and solids removal. Any reduction you make in the volume of effluent discharged is reflected in an immediate and proportionate reduction in the first two components. It has no effect on the third component because any reduction in volume is exactly cancelled out by the increased concentration of contamination in the reduced volume. Similarly, it has no net effect on the fourth component.

Spot samples taken by dipping a sample bottle into the effluent drain for a few seconds are still relied on by many water companies, despite the fact that this gives a hopelessly unrepresentative picture of the contamination you are discharging to the sewer. If sampling occurs just at the point when main washes are being dropped, then a high degree of contamination will be reflected in your charges, whereas in practice these will be diluted over the day with the high volumes of rinse water, perhaps dropped only minutes later.

A much fairer assessment is obtained by installing automatic proportional sampling, with a variable flow taken into the sample bottle over say the working day, which rises and falls with the flowrate to drain. This enables a greater sampling rate when high flows of relatively clean rinse water are being discharged, so it should usually result in lower bills. However, this does call for investment in a flume, the water level in which is used to vary the sampling rate.

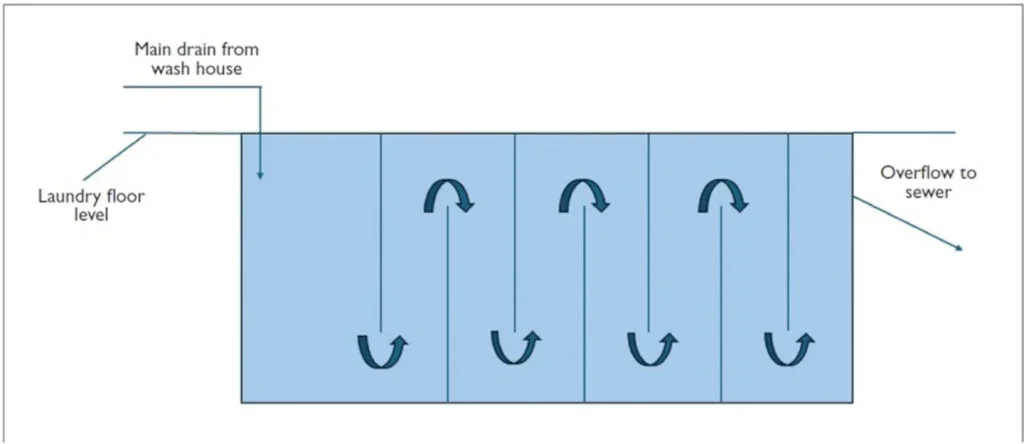

Solids in laundry effluent can be economically removed using a settlement pit. Although a large empty pit can remove some or sometimes nearly all solids, this is always prone to bypassing. Warm dirty wash water tends to rise to the surface and flows preferentially over the outlet weir carrying some of the worst contamination with it.

The solution to avoid this and minimise the volume of the settlement tank is to fit a series of baffles, arranged so as to extend the flow path and mix the contents. The tank has to be cleared of sludge regularly, a tedious manual task, so the baffles should be easily removable.

Hazardous contaminants, typically involving heavy metals such cobalt, manganese, mercury and chromium for example, together with fibres such as asbestos and glass, require separate specialist consideration and were considered in some detail in our October issue.

Conclusion

Modern water and effluent management calls for some agile management and the opportunities revealed should now be seized. There are operating cost and productivity benefits that really merit the time and effort.