There is a bewilderingly wide range of textile constructions available in the worldwide marketplace and little to guide the rental launderer to enable maintenance of stocks at a consistently economic price to meet the quality demands of the ultimate user.

In most countries this gap has been filled by knowledgeable distributors, able to source goods worldwide and stock large quantities of textile items at competitive prices, and who constantly strive to deliver consistent quality of rental performance.

This month we look at the basic knowledge needed by far less technical launderers, to have a sensible conversation with their suppliers, in order to avoid some of the pitfalls which bedevil our rental industry.

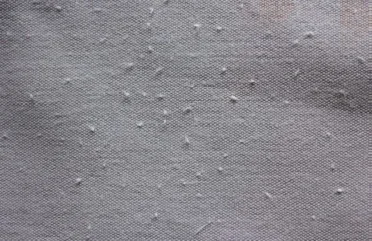

De-seeding is usually carried out in a cotton gin situated near to the fields in which the cotton is grown. The cotton gin revolutionised cotton production and enabled automation of opening out the cotton boll and de-seeding, using wire teeth on a rotating drum. Failure to de-seed properly results in little, almost invisible, seeds being incorporated into the final yarn. These burst after one or two good launderings to cover the cloth with tiny brown seed pods, which can be seen with the naked eye or under slight magnification. These are not contamination in use or in the laundry – they result from an undiscovered manufacturing defect. They will not improve with multiple washing.

Cotton fibres differ considerably in length, strength and diameter, depending on the source and the variety of cotton they come from. The longest and strongest fibres come from Sea Island or Egyptian cotton, but the geographical names are misleading as these can be grown around the world now. The varieties used to produce the largest volume of the cotton used for most rental applications yield a range of fibre lengths. The seeds, the very short fibres and other trash are removed in the cotton gin, and the efficiency of this is reflected in the number of seeds remaining and the percentage of very short fibres going forward to make spun yarn.

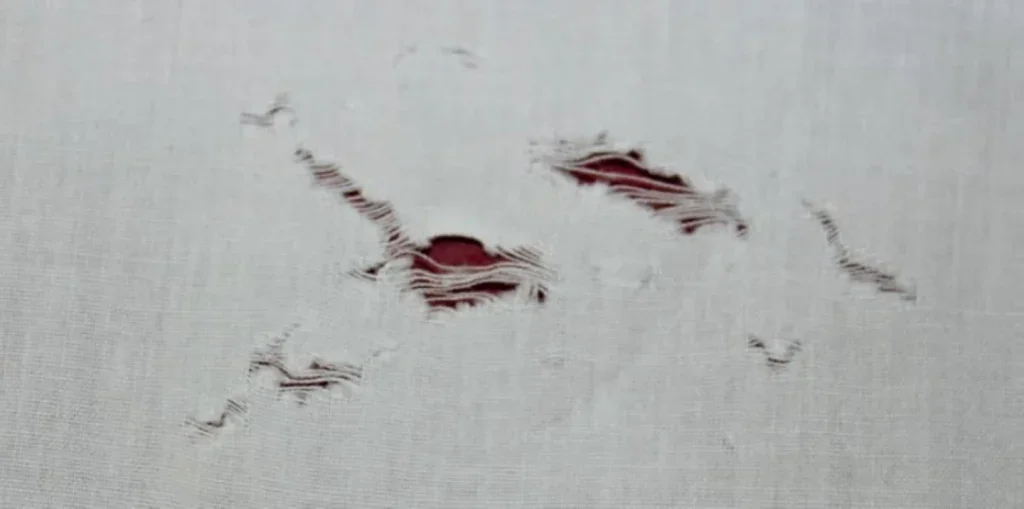

Pilling or bobbling is the result of an excessive quantity of short fibres in the spun yarn. These are difficult to retain if the rental use involves abrasion, such as a hotel sheet, towel or pillow, or workwear garment. Rubbing encourages the short fibres to migrate to the cloth surface where they agglomerate to form tight discrete clumps of fibres, usually held to the textile surface by one slightly longer fibre. This makes them nearly impossible to remove, even by very thorough laundering and the only remedy is return to the supplier for refund. Increasing the twist on the yarn often reduces the propensity for pilling, but this makes the yarn harder and less attractive for the ultimate user. Conversely, the use of too low a twist can cause a fabric with an otherwise suitable range of fibre lengths to exhibit pilling.

International Standards (ISO), in 2014, published a method of test for pilling (see ref. 1) to assist purchasers of large quantities of textiles. It provides considerable help to distributors of rental textiles importing from foreign mills and could also be used in purchase contracts by large rental operators regarding settlement of any dispute concerning the unwanted appearance of pilling.

Spinning involves imparting a twist to the strand of fibres to create the final yarn for weaving. Ring spinning is the traditional technique in which the spool rotates to twist the yarn, while in open end spinning the spool does not need to rotate. Ring spun yarns are generally regarded as superior in evenness and quality, but they are more expensive to produce. Open end spinning enables much higher productivity and hence lower cost, and it is also able to produce a strong yarn from a broad range of fibre lengths. The process rejects any trash continuously as the machine runs. Most rental textiles employ open end spun yarns, with perhaps only a few end-uses preferring ring spun. For example, a fiveor six-star hotel might specify towelling made using the softness of ring spun yarns.

The number of ends and picks in the fabric determines the weight of the fabric per square metre, but ideally the launderer wants the cloth also to be balanced, with the number of picks similar to the number of ends. This improves the stability of the sheets and pillowcases going through the ironer. Equally importantly, the launderer needs the weft threads to be straight and at right angles to the warp, which is how they come off the loom. Sometimes the tensions on the finishing line distort the fabric so that the weft threads lie at different angle or even worse, the weft threads follow a curve. This causes further distortion as the items go through the ironer. The greatest problems arise with duvet covers, if the curve or angle on the weft threads is different on the two sides of the duvet cover, it can sometimes be virtually impossible to iron the cover to produce a perfect finish, however it is fed and however well-tuned the ironer is.

Yarn preparation for weaving often involves applying sizing to the warp yarns, reducing friction and thus enabling higher shuttle speeds and lowering the weaving cost. It is important that in cloth finishing this sizing is washed off, otherwise it can seriously interfere with the laundering process. For example, the presence of PVA starch (a popular ingredient) in the warp sizing can lead to cracked ice creasing on sheeting. The very tight creases cannot be removed by the laundry ironer, and they spoil the stock for the first twenty washes or so. If the sizing is washed off on the cloth finishing line before the final stenter, then it comes away very easily in warm water, before the heat in the stenter can set it onto the cloth.

Bleaching is an essential feature of cloth production to make the many shades of natural cotton pure white, ready for use as white textiles or for dyeing to coloured goods. Bleaching is achieved by chemical oxidation of the natural dyes in raw cotton using either sodium hypochlorite or, more commonly, hydrogen peroxide. Both of these useful bleaches have one feature in common – they will degrade and weaken cotton if used at the wrong temperature or at too high a concentration or for too long a contact time. The result is premature weakening of the cotton yarns, so that instead of getting to a target of say 200 wash and use cycles, the rental operator only gets perhaps 40 or 50. The British Standard test for measuring the degree of damage that new cotton cloth exhibits from manufacture uses a method which employs liquid mercury and is no longer acceptable for safety reasons. However, a revised, safe method of test is now available, although it is not yet a British Standard. It is used by leading distributors and rental operators in the UK (and increasingly overseas) to gauge the degree of degradation which new cotton cloth has endured in manufacture.

Tinting of some new batches of fabric is an occasional problem that never seems to get permanently solved, with reports of blue, red, yellow and green shades which appear after one or two washes and get gradually worse before they get better! It is often caused by a conflict between the optical brightening agent (OBA) in the laundry detergent and the OBA put on in manufacture by the cloth finisher. Instead of producing pure white light and enhancing the brightness and liveliness of the fabric, the combination sometimes changes the wavelength of the extra light produced, to give the undesired shade change. The distributor or other purchaser can check each fresh batch using a few test washes, but the disruption to a ‘just in time’ supply chain strategy can be quite severe. The best distributors arrange for this to be checked in the country of production, which is a good solution, but a test couple of washes by the rental purchaser on a single item from a fresh batch is still a good check.

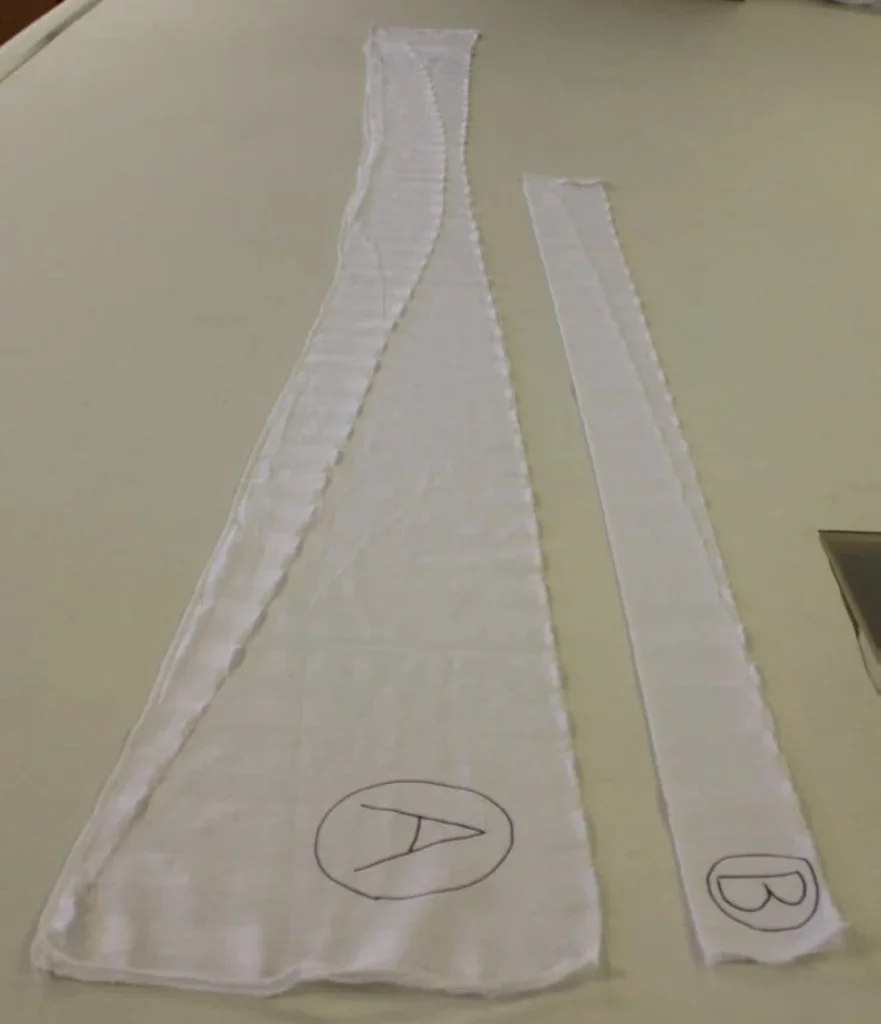

Pillowcase construction is critical when it comes to cutting out from the fabric roll. A pillowcase will always iron best if fed in with the warp threads parallel with the direction of travel through the ironer. In practice this means always having the warp running down the length of the pillowcase. Occasionally, a cut, make and sew manufacturer will cut pillowcases to make the most efficient use of the full width of the fabric roll, regardless of the direction and an entire batch of pillowcases will be virtually unusable for contract or rental, because the ironed finish is so poor (with severe and unpredictable creasing).

Conclusion

The problems described are not once in a lifetime earthquakes or tsunamis – they are happening every day, and they are costing rental operators significant sums to correct. The importance of linking to a reliable and expert distributor has never been greater. The greatest dangers seem to come when a purchasing manager is offered a job-lot of new textiles (perhaps to satisfy an urgent shortage) and buys it, based on a visual inspection (or perhaps no inspection at all) from a hitherto little used or unknown supplier. The rental operator can destroy overnight a hardwon reputation for reliability and quality. Now at least you have some of the tools to assess the risks and avoid some of the pitfalls!