The damage was caused by a pipe burst, which resulted in a ceiling collapse. The main feature was contamination of many items by fine, white, particulate debris, from the building materials used. The problems centred on disappointing outcomes with the designer garments in the consignment.

Restoration was attempted after significant delays, during which the textiles were left in contact with the contaminating water and debris. This is a major problem with a great many restoration contracts and readers are advised to develop a close relationship with the insurers with whom they deal, explaining that the chances of success are greatly reduced by delays.

The cleaner elected to use a purposedesigned wetcleaning system, with water as the main cleaning medium. In the event of heavy and extensive contamination with waterborne soiling, a water-based process is frequently the best option open to the cleaner, because this type of soiling does not normally respond well to drycleaning. However, in this particular case, the plasterboard debris appears to have formed a particulate sludge which had penetrated deep into the textiles. With the benefit of hindsight, this particular type of soiling, because of its particulate nature, would have responded much better to drycleaning (provided that it had first been allowed to dry out completely). This would have provided the much higher level of mechanical action needed for the breakup and removal of this partially solidified sludge. Drycleaning would probably need to be followed up by a water-based process, to give the best chance of removing any staining or water marks resulting from the dissolved water-soluble matter remaining after drycleaning. This would also provide the best chance of removing any staining brought about by the delay in cleaning.

An additional advantage of drycleaning first is that some items may respond very well and be easy to finish immediately to a high standard.

Removal of fine white particulate debris

The white particulate contamination is almost certainly from the collapsed ceiling plaster and plasterboard. This would be expected to form a sludge with the water and dry to leave noticeable white powdery deposits. Restoring articles thus contaminated i demands that, if drycleaned prior to wetcleaning, the items must be bone dry before drycleaning, to avoid any risk of felting shrinkage on animal hair fabrics and problems associated with fusible interlinings. By drycleaning first, the cleaner will avoid any swelling due to water of animal hair and cellulosic textiles (which is likely to hinder removal of the particulates). Also, drycleaning would provide the muchneeded high level of mechanical action required for the removal of the particulates.

Failure to achieve removal of the particulates seems to be the major problem here, with multiple examples of speckling by white particles and the survival of entire white patches on the finished goods. It is quite possible that any remaining superficial white patches could have easily been removed with the spotting table air gun and it is highly likely that provided items are bone dry, the problem of the heavy white deposits on the robust items could be resolved by drycleaning using a good quality detergent and a normal drycleaning cycle designed for garments labelled .

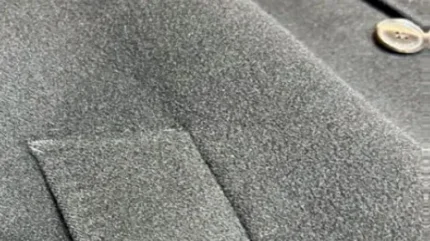

Shrinkage and harsh handle

The process used for the cashmere coat was incorrect. Cashmere demands a low wash temperature and very low mechanical action. It was the mechanical action in this case which caused felting of the cashmere and consequent shrinkage and harsh handle. Wetting cashmere causes the scales on every individual fibre to rise, so that they take on the appearance of a barbed spear. When the cage in the wetcleaning machine is rotated, the mechanical action will push some of the fibres together, but they will not slide apart. The shrinkage can sometimes be rectified by strong tension in pressing, so interlocked fibres are torn apart, but this will not cure the harsh surface and matted appearance. The garment is irreversibly damaged.

Whitening of the seams on many garments

The restoration company’s finishing equipment was not in tip-top condition, judging by the incidence of whitening or fading along the multi-thickness seams. Localised fading of this type can also occur as a consequence of normal wear (which can loosen dyes at the fabric surface, allowing these to be washed away by the cleaning fluid, either water or drycleaning solvent). The fact that most of the multi-thickness seams on these garments are affected along their entire length would indicate that much of the fading occurred during pressing. This can occur if too much pressure is applied, but a more common cause is inadequate resilience in the press clothing (the compressible padding which must be capable of accommodating multi-thickness seams, to avoid this particular fault).

Wrinkling around the armhole seam and bubbling of the jacket front

The wrinkling around the armhole seams on the new designer suit is caused by relaxation of manufacturing strains, either from clothmaking or from garment manufacture. The elliptical armhole seam of the suit involves stitching a padded and fused shoulder and front assembly to a thin sleeve fabric and lining, which inevitably requires considerable tensions. These may relax out in cleaning, resulting in unsightly wrinkling and pucker. This can only be rectified by skilful pressing, using steam and tension, in conjunction with the correct use of vacuum, which this jacket does not appear to have received.

The visible and tangible wrinkling across the fronts of the new suit has a different cause. It results from shrinkage, during cleaning, of the interlining fused to the reverse of the jacket fronts. This usually results from slight mismatching of the relaxation potentials of the different layers in manufacture. It is a common problem with many designer suits, and it demands considerable skills in pressing to rectify it. Some cleaners do not accept some designer suits for this reason.

Damage to designer buttons

The damage to the buttons described is because, as in many designer ranges, the buttons are made in a short run, specifically for one design. Experienced cleaners recognise the requirement to always either protect designer buttons with aluminium foil (or button protectors) or to remove the buttons and sew them back on after cleaning and finishing. This and the other extensive problems described inevitably raises the question as to whether the restoration contractor was properly equipped, and the staff trained and competent to handle and restore classifications and items that demand extremely high finishing skills and detailed knowledge of how textiles and trims respond to the various cleaning and finishing systems.

Loss of colour to leather accessories

The result for this black leather belt emphasises the difference between wet or drycleaning of textiles versus recovery of leather or suede items. This belt carries classic symptoms of mild abrasion in normal wear which has loosened the dyes in the leather surface at the points where the leather has been rubbed against the metal designer trim. As is quite common, the loosened colour has been flushed out in the cleaning process. A professional leather cleaner would simply restore the lost colour by localised touching up with special leather recolouring dyes or pigments and this is what is needed for successful restoration of this grain leather belt. The restoration contractor does not appear to have done this. There is nothing apparently wrong with the cleaning process – the restoration is simply incomplete

Conclusion

Restoration can involve large numbers of items and is a very worthwhile addition to any cleaner’s range of services. Successful execution and a profitable outcome depend on the necessary associated skills, both in cleaning and finishing. This month we have touched on just a few of these skills and some of the essential features of an effective relationship with insurers and the ultimate customer. The Editor would be interested to hear further examples of your experiences.