Removal of harmful contaminants from workwear for every occupation has become a feature of modern life and rental garment operators have been quick to respond, with particular reference to allergens on food industry workwear, for example. Here, we look at the problems facing workers who come into contact with chemicals and other hazards. Concerns have been raised about heavy metals and dangerous fibres, both asbestos and glass. Forward thinking rental garment operators are already putting plans in place to address these.

Many operatives experience only slight exposure to compounds containing cobalt, chromium, mercury, lead and some of the thousands of organic carcinogens. End users like the fire service could now be seeking an industry-wide approach on the how to tackle the risks associated with these. In this edition we offer some suggestions on how to cope with an increasingly demanding clientele and to offer justified assurances that the decontamination level achieved is meeting customer requirements. The first point to recognise is that the demand from the customer base is ever evolving and decontamination rather than simple cleansing could be the new ‘name of the game’.

Asbestos and fibreglass

The full impact of the considerable popularity of asbestos fibre in building construction and insulation during the last century is still being felt, with factory workers and healthcare staff, for example, concerned, as old buildings crumble and release potentially harmful fibres. Where these are released in a fire or during building work, they can become lodged in the outer surface of an operator’s clothing and need to be removed. They are usually held by simple mechanical entanglement and can be removed by a professional, purpose-designed wash process. They come away with intelligent detergency and are prevented from re-depositing on the fabric (to which they tend to be attracted by electrochemical charges) by the use of strong suspending agents in the wash chemistry.

The question arises as to how a rental operator can verify that there are minimal hazardous fibres left on the fabric. The best way of doing this is by occasional examination of a typical frontal area on one garment from a batch, using a good microscope, set up to focus on say an area 25mm x 25mm. Other techniques can be borrowed from cleanroom technology, using vacuum to remove fibres and particles from the surface of a test garment filtering this over a graticule and examining the contamination recovered using high magnification. Dangerous residual fibres of asbestos or glass can be recognised visually under magnification.

Organic carcinogens

Some very concerning university research results, reporting the higher incidence of death and serious disease (particularly cancers) in retired firefighters, have already been published by LCN (see issues from June 2018, Jan 2020 and Dec 2023). There is a strong possibility that organic carcinogens released or formed in a strong blaze and then absorbed through the skin or by inhalation could be a contributory factor. This is being addressed by the latest designs of layered fire-wear and by the policy of decontaminating used garments immediately after use. Outer layers are now removed at the scene of the incident wherever possible, and not allowed to come into human contact before decontamination.

There are a great many possible carcinogens in this category. It is possible to try to analyse for each of these. However, a more pragmatic approach is to uprate the power of the decontamination process by the incorporation of a broad range emulsifier able to cope with all types of oily or fatty organic compounds. Chemicals which are either miscible with or soluble in water are not usually a problem for decontamination by laundering – it is those with an oily or fatty characteristic which might survive the wash.

In order to be certain that the power of the wash process is sufficient to reduce the risk of any organic contaminant surviving the wash, two checks are essential. Firstly, the wash process must be fully validated using garment batches known to be contaminated. This currently forms part of an LTC research program. Secondly, there should be regular simple checks to verify process power using, for example, EMPA test swatches. LTC have already followed the general principles of this approach and refined it for allergen control on food industry workwear, with eminently successful results which are now being widely implemented.

Where the precise hazardous contamination is known, it might be necessary to make regular checks on either a garment taken at random or on plain white cotton test swatches, using appropriate analytical methods, able to pinpoint a particular chemical of concern.

Heavy metals

These are loosely defined as metals with high density, high atomic weight or high atomic number. They include cobalt, manganese, chromium, lead and uranium, for example. They are hazardous because they can be absorbed into the human body quite readily, especially if they are in the form of a soluble salt or combined in a gaseous compound. Lead, for example, affects the brain, heart, lungs, kidneys and bloodstream, and lead poisoning is cumulative.

Tetraethyl lead was added to petrol in the UK in the 1920s to reduce engine preignition or ‘knocking’. From 1970 until the end of the century, it’s estimated that about 140,000 tonnes of lead were released into the atmosphere from tailpipes, in the UK alone. However, since 1999, using lead in fuel has been banned in the UK and most countries worldwide due to evidence that exposure to lead causes developmental problems in children and cardiovascular, kidney, and reproductive problems in adults. National legislators are quite rightly keen to ensure no repetition of this with other potential contaminants.

Decontamination of workwear contaminated with any heavy metal usually demands a laundering process with controlled alkalinity and other specific features, to solubilise the target metal or metals. Users can then be expected to request process validation, together with routine assurance checks that the process power continues at the level needed.

Mercury

Mercury vaporises at 356C, so vapour is generated in many fires, including industrial, commercial, educational and residential. Even a broken thermometer or barometer can give rise to concern – the safe exposure limit for mercury can be as low as one part per billion (1 ppb)! The problem is compounded by the fact that mercury has a relatively high vapour pressure throughout the temperature range.

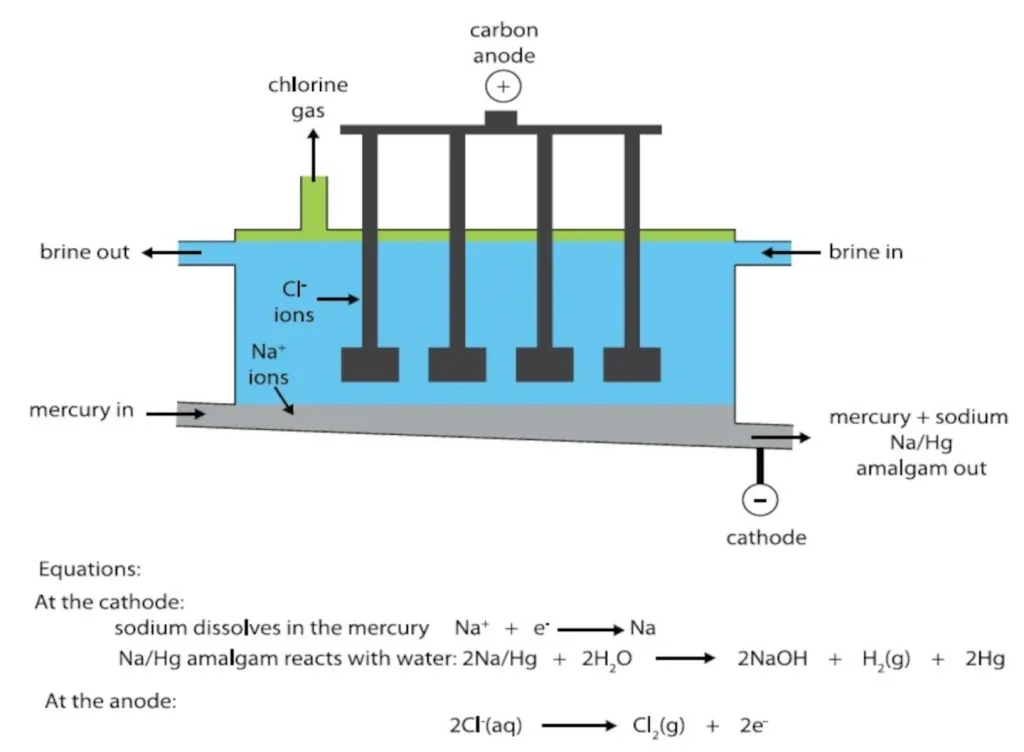

If there is any chance at all of mercury contamination on a batch of fire-wear for example, an effective laundering process can be designed to deal with this. This is also absolutely essential for operatives manufacturing chlor-chemicals based on electrolysis of brine (which uses a liquid mercury electrode). Protection systems for some outboard motors also rely on a sacrificial mercury anode, to prevent corrosion of aluminium components, for example, so even a boatyard blaze can result in serious garment contamination.

Elemental mercury on workwear can be expected to form very tiny droplets, which in a correctly loaded washer extractor might reasonably be expected to go to drain at the end of the stage, because they are much heavier than water. However, relying on this for complete elimination might be overoptimistic (given the danger of only 1 ppb in the garment atmosphere), so designing the wash chemistry to ensure solubilisation is the much-preferred technique.

Chromium

Chromium ions can exist with two distinctly difference valencies – Chromium (III) and Chromium (VI). Chromium (VI) is by far the most poisonous to humans and because it can occur (unintentionally) on chromium alloys in electronic and microelectronic items, there are tight regulations controlling its presence and relatively simple methods of test for detecting it on metal surfaces. These tests might well work on textiles and if so would provide one quick and inexpensive method for the garment rental operator to provide justified assurance to the workwear customer and individual wearers. This would require LTC to conduct some further R&D work to establish a suitable method for customer assurance.

Hazardous effluent

The additional challenges for rental operators could well lie in the potential hazards in the effluent being discharged in the future. Water companies treating laundry wastewater can be expected to take a very dim view of anything which might disrupt their treatment processes, especially if it damages the bacterial action required for purification. Rental operators contemplating serious decontamination services should in the first instance examine the small print of their contract with the water company, which should offer some limits on heavy metals such as lead, cobalt and chromium and guidance in many other areas. This is something LTC are regularly commissioned to conduct.

In the first instance, any organisation entering the market for decontamination should be prepared to install, at the very least, a settlement system, with a residence time sufficient to allow settlement of, for example, liquid mercury droplets or glass fibre. This will probably be around 4 hours, provided the system is fitted with baffles, to discourage dead zones and surface bypassing. Then, with a suitable checking regime, it may prove possible to discharge the liquid as quite acceptable waste to the public sewer, whilst arranging for the sludge at the bottom to be collected by a specialist hazardous waste contractor.

Conclusion

Having studied this article, some readers will be asking themselves “What business am I in? Do I want to be a simple launderer, serving hospitality, for example, or have I got a better future offering decontamination?” That is the right question, but answers will vary widely; there is no ‘right’ answer, but there is an optimum one for every organisation and it could make a critical difference to your future.